Reflections from Hot topic sessions

- Fighting global threats to respiratory health: how to make a difference

- Prevention in focus: A 360° View from global health to local practice

- Importance of the exposome in prevention and treatment of chronic lung diseases (see also separate summary)

Clean air – human right that few can utilize

Non-communicable diseases remain the leading cause of death and disability in the European Region, most of them are preventable. According to a report from WHO Europe, 60% are preventable through reducing exposure to risk factors and public health interventions. In Europe, every fourth adult uses tobacco,1 making both smoking cessation and strengthened tobacco control essential for preventing diseases.

Air pollution – 2nd leading global mortality risk

Air pollution (including indoor and outdoor pollution and super-pollutants such as ozone and nitrous oxide) is considered to be the second leading risk factor for death globally according to data from IHME 2021.2 Air pollution increases the risk of illness and death from multiple major diseases such as COPD, diabetes, lower respiratory infections, lung cancer, stroke and ischemic heart disease and has been associated increased risk of Parkinson’s, Alzheimer, dementia, autism, ADHD and breast cancer, according to Kristie Ebi, Professor of Global health at University of Washington, USA.

Why particulate matter matters

Long-term exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) is particularly harmful as it crosses the lung barrier and enter the blood stream to reach multiple organs. A growing body of evidence also points out fine particulate matter (PM2·5) from wildfire smoke as considerably more harmful to human health than PM from other sources.3 EU data shows that wildfires in 2025 so far have burned more than 1 million hectares in EU countries, the highest value ever recorded since 2006.4 These fires has emitted massive amounts of particulate matter and carbon dioxide that can travel long distances without caring about national borders. Wildfires are both a consequence of climate change, and a cause.

Clean air – a luxury item?

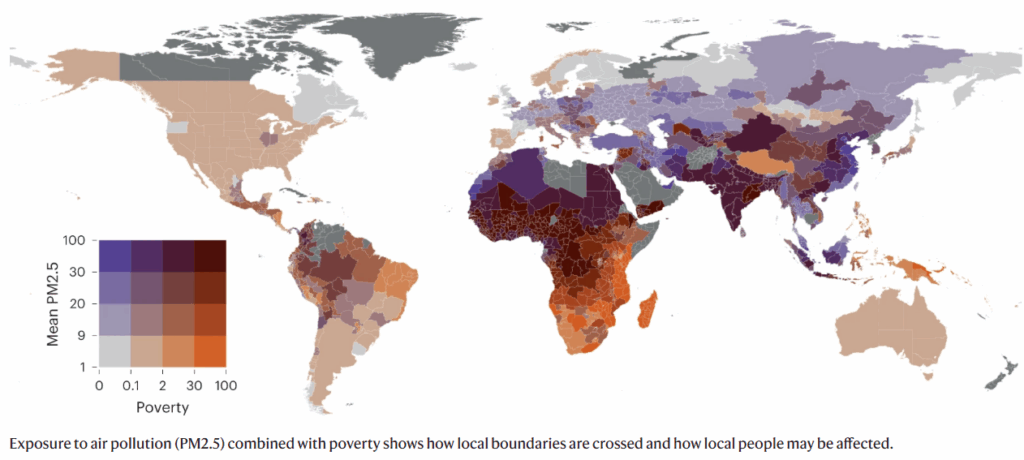

South Asia, Africa and Middle East are most affected by air pollution and it’s clear that the poorest areas of the world has the highest exposure to particulate matter.5 In wealthier areas, regulations have been put in place to successfully reduce the exposure of air pollution. A third of the global deaths due to air pollution occur in Asia,2 where the population are exposed to high levels of particulate matter coming from combustion of coal and biomasses. About 3.2 million people a year die prematurely from burning biomasses to heat homes and cook food, largest burden falling on women and children.6 Reducing sources of indoor and outdoor pollution, e.g. by replacing open-fire cooking with clean stoves, would not only significantly impact health and well being, but also reduce emissions contributing to climate change.

Indoor pollution: Particles, mould and pest infestations

Indoor air quality may in part be impacted to proximity of heavy traffic and how well it is maintained to address/prevent mould, allergens, particulate matter and pest infestation (dust mite, cockroaches). Even in high income countries, there is an inequity in indoor air quality. Low income households might not have the means or possibility (e.g. rented housing) to maintain the house to avoid household risks, and may not have the possibility to relocate to better housing. Visible mould and mould odour in the home is associated with the development of asthma.7

We can tackle respiratory hazards

Many preventable respiratory hazards are both a cause and a consequence of climate change. Mary Rice, Harvard University, Boston, USA talked about scientific foundations for respiratory health and reminded us that fighting climate change is an important part of reducing burden of disease from respiratory diseases.

- Smoking cessation works – not only to prevent lung cancer but also to improve respiratory health and is cost-saving for the society.

- Vaccination – influenza vaccine reduces the risk for all-cause mortality

- Improved indoor climate – In sensitized children, home environmental interventions (allergen-impermeable covers, using HEPA filters in vacuum cleaner, air purifier, pest control, education on mold/moisture control) reduce asthma symptoms. Studies on home use air purifiers are ongoing.

- Managing peak exposures, e.g. wild fires – Given the toxicity of air pollution from wildfires, using HEPA filters or N95 for outdoor exposures could potentially have benefits, but studies of interventions to manage high exposure to pollutants are missing .

- School and workplace air pollution – improving air quality in schools and workplaces to lower harmful exposure is important given the amount of time spent in these locations. Measures to eliminate or at least limit risks for exposure of mould, mites and particulate matter should be taken.

- Smoke-free laws – examples from England8 and Scotland9 banning smoking in enclosed spaces to protect people from secondhand smoke, are linked to reduction in asthma hospitalizations, both pediatric and adult.

- Traffic reduction – several examples were given, including Stockholm’s congestion pricing and London’s ultra low emission zones, where city-level traffic intervention not only lowered levels of pollutants, but also a reduction in respiratory events.

Word of advice from Mary Rice was to focus on health equity for our prevention efforts: prioritize highest-risk patients and highest-burden communities, this is where the benefits of an intervention will be the greatest.

Erika Petersson

Medical Digital Content Manager, Chiesi

References

- https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/tobacco

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Burden of Disease 2021: Findings from the GBD 2021 Study. Seattle, WA: IHME, 2024.

- Alari A, Ballester J, Milà C, et al. Quantifying the short-term mortality effects of wildfire smoke in Europe: a multicountry epidemiological study in 654 contiguous regions. Lancet Planet Health. 2025;9(8):101296. doi:10.1016/j.lanplh.2025.101296

- https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/what/civil-protection/wildfires_en

- Gupta, J., Liverman, D., Prodani, K. et al. Earth system justice needed to identify and live within Earth system boundaries. Nat Sustain 6, 630–638 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01064-1

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health

- Caillaud D, Leynaert B, Keirsbulck M, Nadif R; mould ANSES working group. Indoor mould exposure, asthma and rhinitis: findings from systematic reviews and recent longitudinal studies. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(148):170137. Published 2018 May 15. doi:10.1183/16000617.0137-2017

- Millett C, Lee JT, Laverty AA, Glantz SA, Majeed A. Hospital admissions for childhood asthma after smoke-free legislation in England. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):e495-e501. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2592

- Mackay DF, Turner SW, Semple SE, Dick S, Pell JP. Associations between smoke-free vehicle legislation and childhood admissions to hospital for asthma in Scotland: an interrupted time-series analysis of whole-population data. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(8):e579-e586. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00129-8

17047-03.10.2025